In earlier articles, we have discussed the business of building recommendations: see Horses for Courses, and Hello Rubber, Meet Road. These have focused largely on offline recommendations that are generated and sent in batch mode; here, we shall focus on the real-time case.

What does it mean to have real-time recommendations? It is intuitive that this question gets asked in the context of a web/app experience, wherein recommender widgets can personalize a customer’s shopping experience. (To be fair, there are also potential offline use-cases, such as when a shopping assistant at a store is armed with recos while talking to a customer, or when a customer’s journey through the physical store is given a personalized fillip through an app that senses location etc. However, let us, for now, focus on the vanilla use-case of adding recommendations to someone browsing on an app in the comfort of their living room.)

Let’s break down what it means, from the following standpoints: input/output, and how the recommendations might be computed. The former has to do with recommenders as an abstraction, and focus simply on what information is available and what the user experience can be like. The latter has to do with how it all gets accomplished.

What we will not focus on in this article: how identity resolution is performed so that we know which customers are doing what (both online and offline), the mechanics of collecting data and serving up recommendations. This article is more to provide a conceptual overview of what this system ought to do.

Input/Output

Recommender systems primarily rely upon information on how customers have historically engaged with products. In offline businesses, the only signal one usually gets regarding a customer’s engagement with a product is the purchase itself. However, in online businesses, softer indications of intent, such as product browse, cart addition, wish-list addition, and search are available to learn from.

Obviously, not all indications of intent deserve the same emphasis – someone browsing a product page is a lot less important than someone adding it to a shopping cart, which in turn is less important than an actual purchase. The relative weight of importance of these signals can either be manually set, or auto-determined based on the proportion of customers who provide them.

The customer’s browsing experience can be personalized in a variety of ways. For instance:

The home page or landing page can contain ‘recommender widgets’ containing recommendations for various scenarios. Since customers approach consumption in different ways, the way in which recommendations are presented to them can also vary; this issue has been addressed at length in an earlier article on recommender systems, titled Hello Rubber, Meet Road.

Recommendations can also be contextual: product pages can contain recommendations to similar or complementary products, as can the checkout page (basically, the online version of “Would you like fries with that?”).

It is also possible to order an existing set of products based on customer preferences. For instance, if my colour preference is blue, then a product listing page for formal shirts could start with the blue shirts, with a few from elsewhere in the colour spectrum thrown up in order to explore if the customer wishes some variety. Similar reordering of a product listing can apply in case of search results as well, thereby improving relevance and therefore conversion rate.

In cases where a hitherto unknown customer opens up the webpage, there needs to be a Plan B in place to serve up generic recommendations while the behavioural signals with respect to that customer’s interests are collected.

It is also possible to envisage an offline+online use-case wherein a customer is sent a marketing message with a personalized link that takes them back to the app, wherein personalized recommendations are served up. Once the customer is on the digital channel, it’s business as usual.

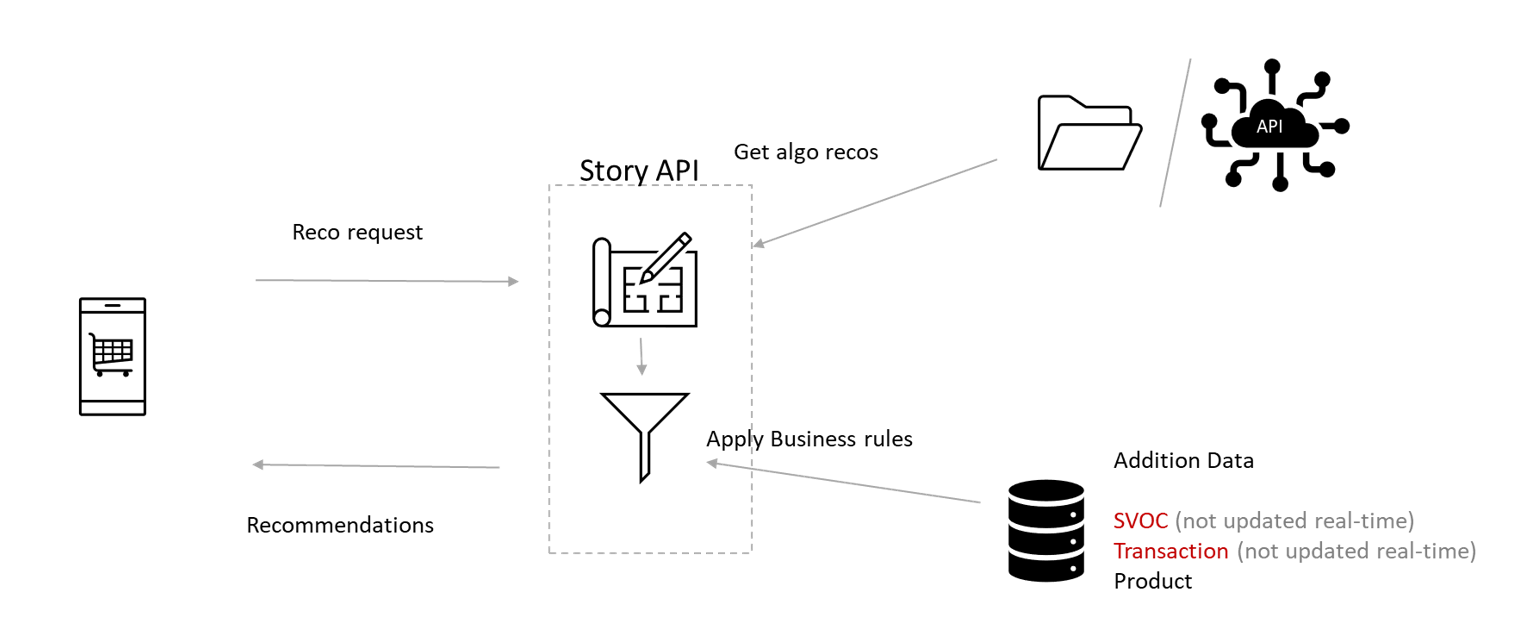

Broadly speaking, these use cases above require a product recommendation engine that can return recommendations to the website, given a use-case id and some additional context such as the customer key, the product key (in case of contextual recommendations), and the id of the use-case being handled.

Algorithms

Now, if a web or app experience has to be personalized, all of this recommender magic has to happen in the short duration between someone clicking on a link and the page loading, or in the time it takes to load the landing page on the app.

Precomputed vs. Real-Time: When to Use Each

This does not necessarily imply that the recommendations have to be computed in that time frame. It is possible that for a number of recommender widgets, the results can be precomputed and served up on demand. For instance, on a product display page, there might be a widget that says “People who bought this product also bought…”. This would require us to analyze co-purchase patterns and arrive at commonly co-purchased items with the one in question. Rather than do this on the fly, one could perform the co-purchase analysis in batch for all products, precompute the recommendations, and simply serve them up. These batches can be as frequent as is required depending on how fast-changing the buying patterns are. This also allows us to use more sophisticated/involved methods and generate better recommendations, while not losing either latency or responsiveness to changing behavioural patterns.

It is possible to have a semi-precomputed use-case, wherein one would like to have a list of personalized recos in a category/sub-category listing page, filtered to that particular category/sub-category. This can be done by precomputing personalized recos for each customer, and then simply applying an ad-hoc filter of the relevant product attribute; if the number of recos remaining post-filter is insufficient, one can fill in the remaining slots based on what is trending.

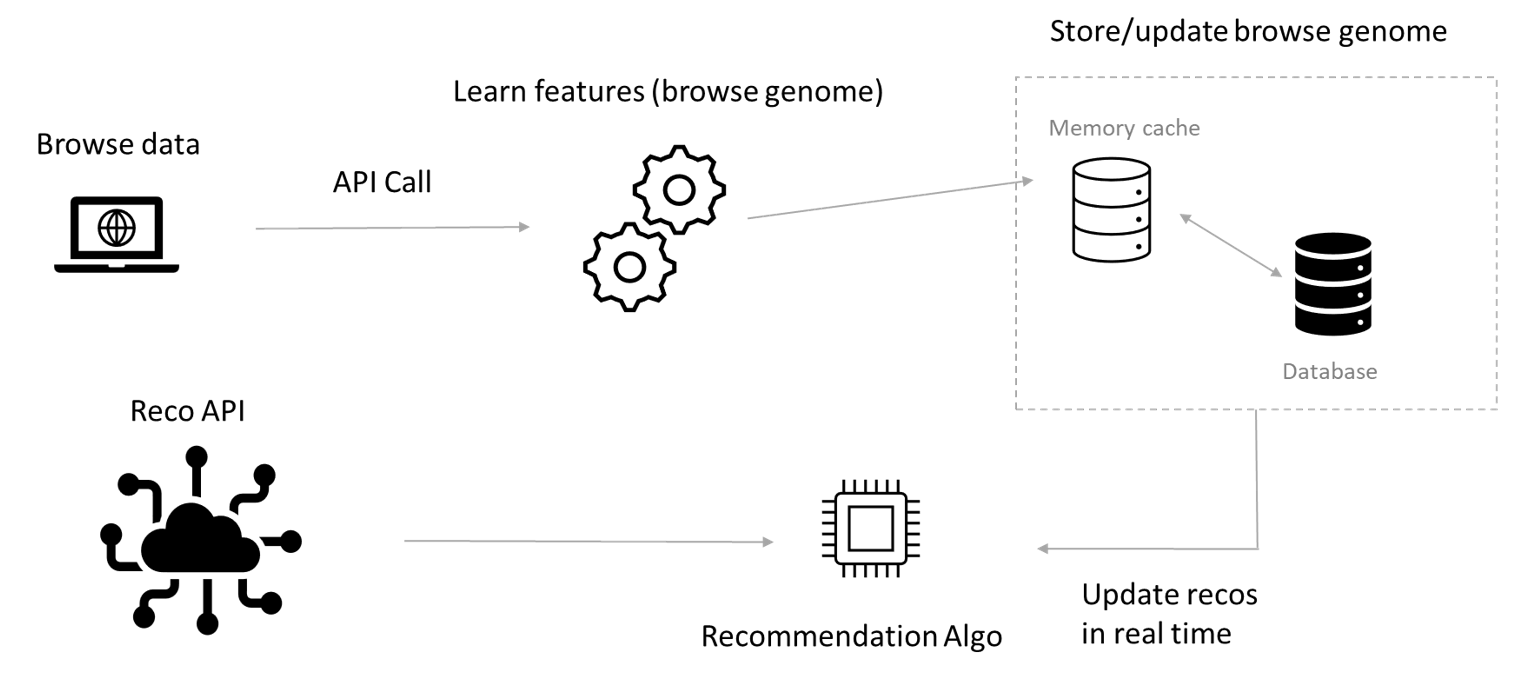

On the other end of the spectrum, a reco widget titled “Based on your browsing patterns” has to be sensitive to real-time inputs on what the customer is looking at, even within the same session. The simpler this algorithm, the faster the response.

For instance, every time a customer visits a product page, a call can be made to a personalization API that learns from this event and updates a browse preference vector, namely a vector of the product attributes that the customer has visited so far; the more often a customer visits products with a specific attribute, the higher the value of the vector element pertaining to that attribute. This aggregate preference vector can then be compared to the attributes of all recommendable products to identify which ones have attributes closest to the ones preferred by this customer. Since these are very simple operations, this algorithm can be implemented with acceptable latency.

Up Next: In Part 2, we’ll discuss the performance of SOLUS’ real-time recommender API and how it can be used effectively to power your personalization strategy.